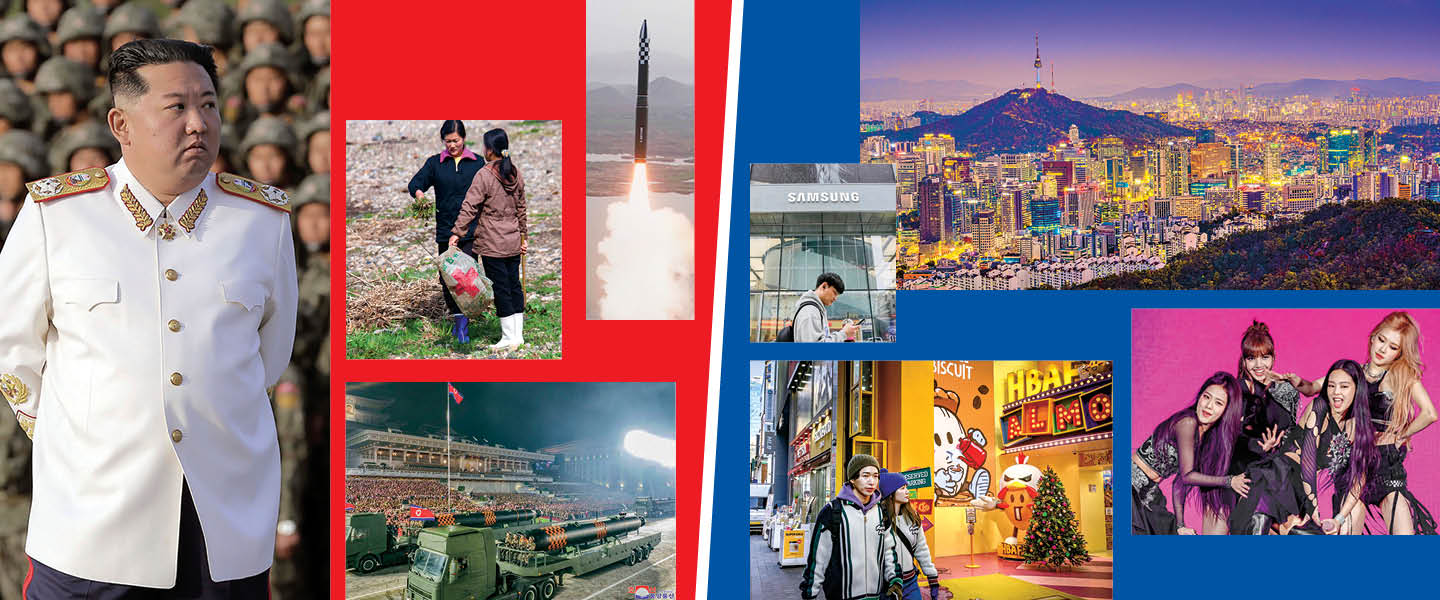

Today, South Korea is a robust democracy with a thriving, high-tech economy. Its products—think Samsung phones and Hyundai cars—are exported all over the world, as are its music, TV shows, and movies.

North Korea, on the other hand, is a repressive Communist dictatorship in which millions face hunger and the government executes political opponents. It has also built up a nuclear weapons program that threatens South Korea and the roughly 28,000 American troops stationed there.

Continually on the brink of conflict, the Korean peninsula presents President Donald Trump with one of his key foreign policy challenges.

South Korea is a thriving democracy. It has a high-tech economy that exports products all around the world. Samsung phones and Hyundai cars are made there. South Korean music, TV shows, and movies are everywhere.

North Korea, on the other hand, is a repressive Communist dictatorship. Millions of people face hunger, and the government executes political opponents. It threatens South Korea with a nuclear weapons program. The roughly 28,000 American troops stationed in South Korea also face this threat.

Always on the edge of conflict, the Korean peninsula presents President Donald Trump with one of his key foreign policy challenges.