You’re just a teenager, so even if you worry about climate change, you can’t do much about it. Right?

Wrong, says 18-year-old Mateo De La Rocha.

“No matter how young you are or what resources you have, you can make a positive impact,” he says.

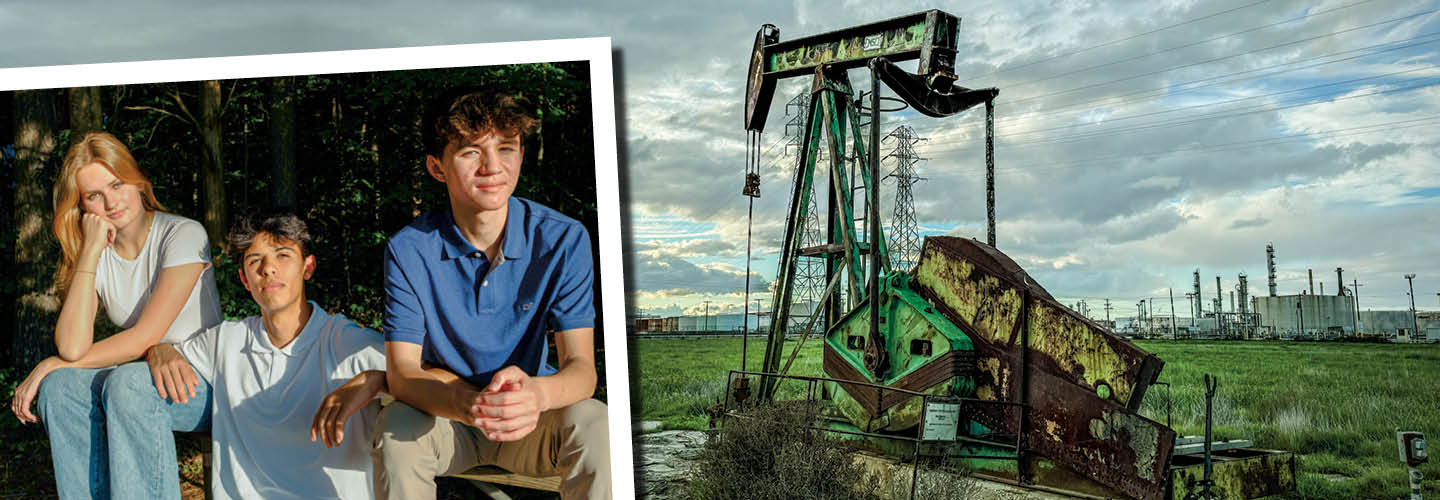

Mateo, who graduated from Panther Creek High School in Cary, North Carolina, last spring, and two friends have founded a group they call the Youth Climate Initiative. They’re trying to convince other teenagers—and anyone else who will listen—that an investment of $25 toward cleaning up abandoned oil wells can achieve the same reduction in greenhouse gas emissions as replacing several gas-powered cars with electric vehicles for one year.

Their group recently raised $11,000 to plug an abandoned well that was leaking gas on an Ohio horse farm. As many as 3.9 million abandoned and aging oil and gas wells—deep holes in the ground drilled by fossil fuel companies—dot the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

When a well is no longer in use, it’s supposed to be closed off with cement in a process called capping or plugging. But many have been left open, often in disrepair, polluting groundwater and leaking toxic gases like hydrogen sulfide into the air. The wells can be extremely dangerous for people nearby.

You’re a teenager worried about climate change. But you think you can’t do much about it. Right?

Wrong, says 18-year-old Mateo De La Rocha.

“No matter how young you are or what resources you have, you can make a positive impact,” he says.

Last spring, Mateo graduated from Panther Creek High School in Cary, North Carolina. He and two friends have founded a group called the Youth Climate Initiative. They’re trying to convince other teenagers and everyone else that cleaning up abandoned oil wells can make a big difference. They say a $25 donation to the cause can achieve the same reduction in greenhouse gas emissions as replacing several gas-powered cars with electric vehicles for one year.

Their group recently raised $11,000 to plug an abandoned well that was leaking gas on an Ohio horse farm. There are as many as 3.9 million abandoned and aging oil and gas wells in the United States, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The wells are deep holes in the ground drilled by fossil fuel companies. When a well is no longer in use, it’s supposed to be closed off with cement in a process called capping or plugging. But many have been left open. They are often in disrepair and pollute groundwater. Uncapped wells also leak toxic gases like hydrogen sulfide into the air. The wells can be extremely dangerous for people nearby.