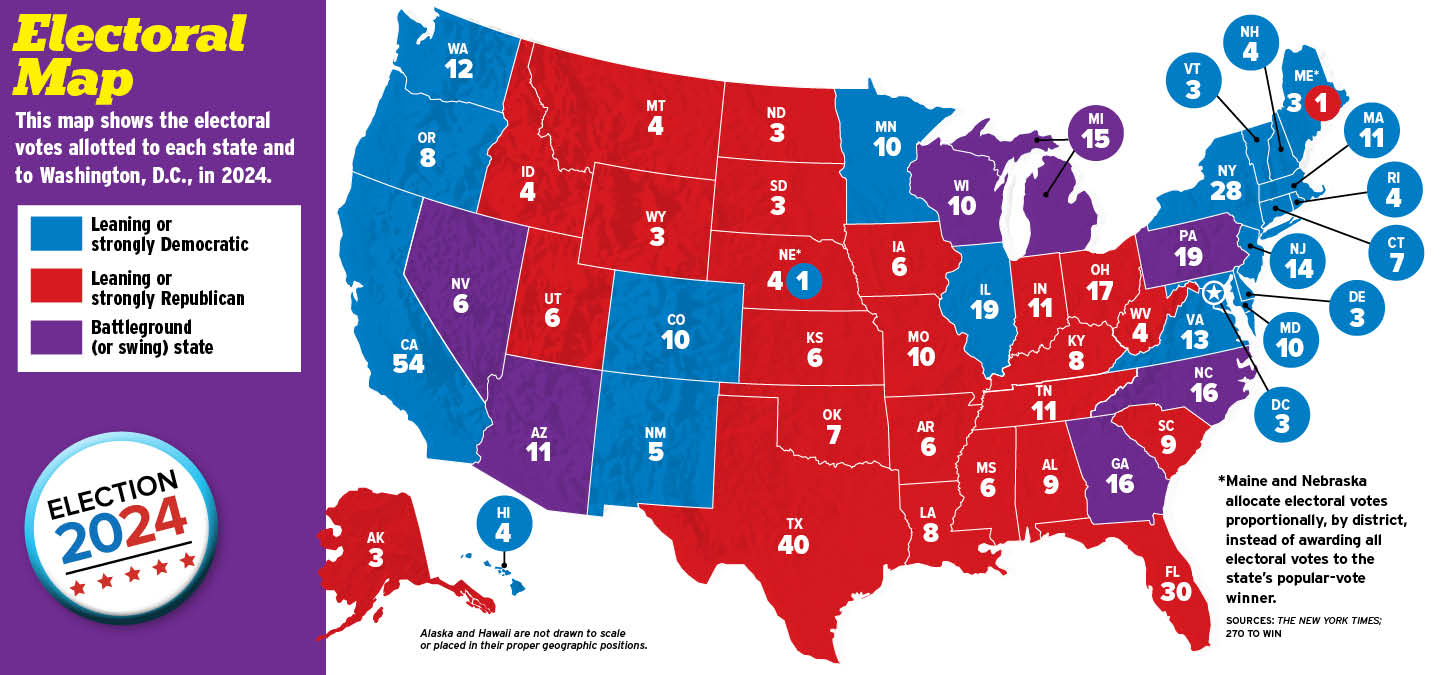

This college doesn’t have fraternities, a football team, or even any classes: It’s just 538 people called electors from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. According to the Constitution, they’re responsible for electing the president and vice president. The winner needs a majority—at least 270—of the 538 electoral votes.

This college doesn’t have fraternities, a football team, or even any classes. It’s just 538 people called electors. They are from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. According to the Constitution, they are responsible for electing the president and vice president. The winner needs a majority, or at least 270, of the 538 electoral votes.