Garlic was dead, and there was nothing Huang Yu could do about it—or so he thought. Hours after burying his cat in a park near his home in Wenzhou, a city in eastern China, the 22-year-old recalled an article he’d read on dog cloning. What if someday he could bring Garlic—who had died in 2018 of a sudden infection—back to life?

“In my heart, Garlic is irreplaceable,” says Huang, who dug up his British shorthair and put the 2-year-old cat in his refrigerator in preparation for producing a clone, an exact genetic copy. “Garlic didn’t leave anything for future generations, so I could only choose to clone.”

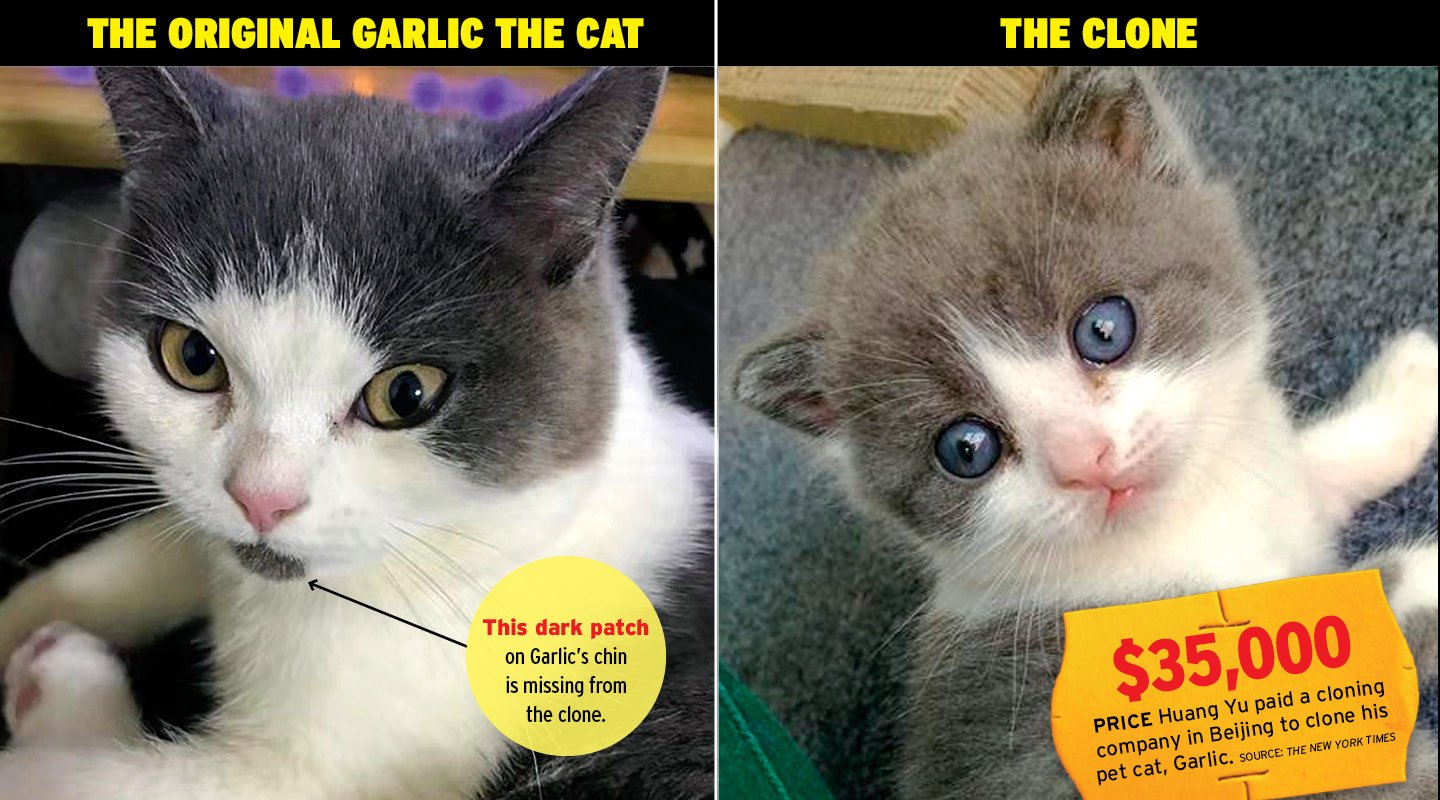

That thought led him to Sinogene, a pet-cloning company based in Beijing. Roughly seven months later, for the price of $35,000, Sinogene produced what China’s official news media declared to be the country’s first cloned cat.

Pet cloning might soon be the latest fad to take over China, but it’s not confined there. People in South Korea and even in the United States have also had their pets cloned. A Texas-based company called ViaGen Pets offers dog cloning for the hefty price of $50,000 and cat cloning for $35,000. (Cloning cats is cheaper because the process is simpler.)

But is cloning pets a good idea?

Garlic was dead, and there was nothing Huang Yu could do about it—or so he thought. He buried his cat in a park near his home in Wenzhou, a city in eastern China. Hours later, the 22-year-old recalled an article he’d read on dog cloning. The cat had died in 2018 of a sudden infection. What if someday he could bring Garlic back to life?

“In my heart, Garlic is irreplaceable,” says Huang, who dug up his British shorthair and put the 2-year-old cat in his refrigerator in preparation for producing a clone, an exact genetic copy. “Garlic didn’t leave anything for future generations, so I could only choose to clone.”

That thought led him to Sinogene, a pet-cloning company based in Beijing. Roughly seven months later, Sinogene produced what China’s official news media declared to be the country’s first cloned cat. Huang paid $35,000 for the service.

Pet cloning might soon be the latest fad to take over China, but it’s not confined there. People in South Korea and even in the United States have also had their pets cloned. A Texas-based company called ViaGen Pets offers dog cloning for the hefty price of $50,000. The company offers cat cloning for $35,000. Cloning cats is cheaper because the process is simpler.

But is cloning pets a good idea?