When she was a senior at High Point University in North Carolina, Brittany Gentilhomme dreamed of renting an apartment and living on her own after graduation in 2017. Instead, she had difficulty landing a job in her chosen field, communications, and had to move back into her parents’ home in Milford, New Hampshire, for three years so she could try to make a dent in the $65,000 she borrowed in student loans. Gentilhomme, now 24, says living with her parents made her feel “like my life was on hold. I didn’t feel like an adult.”

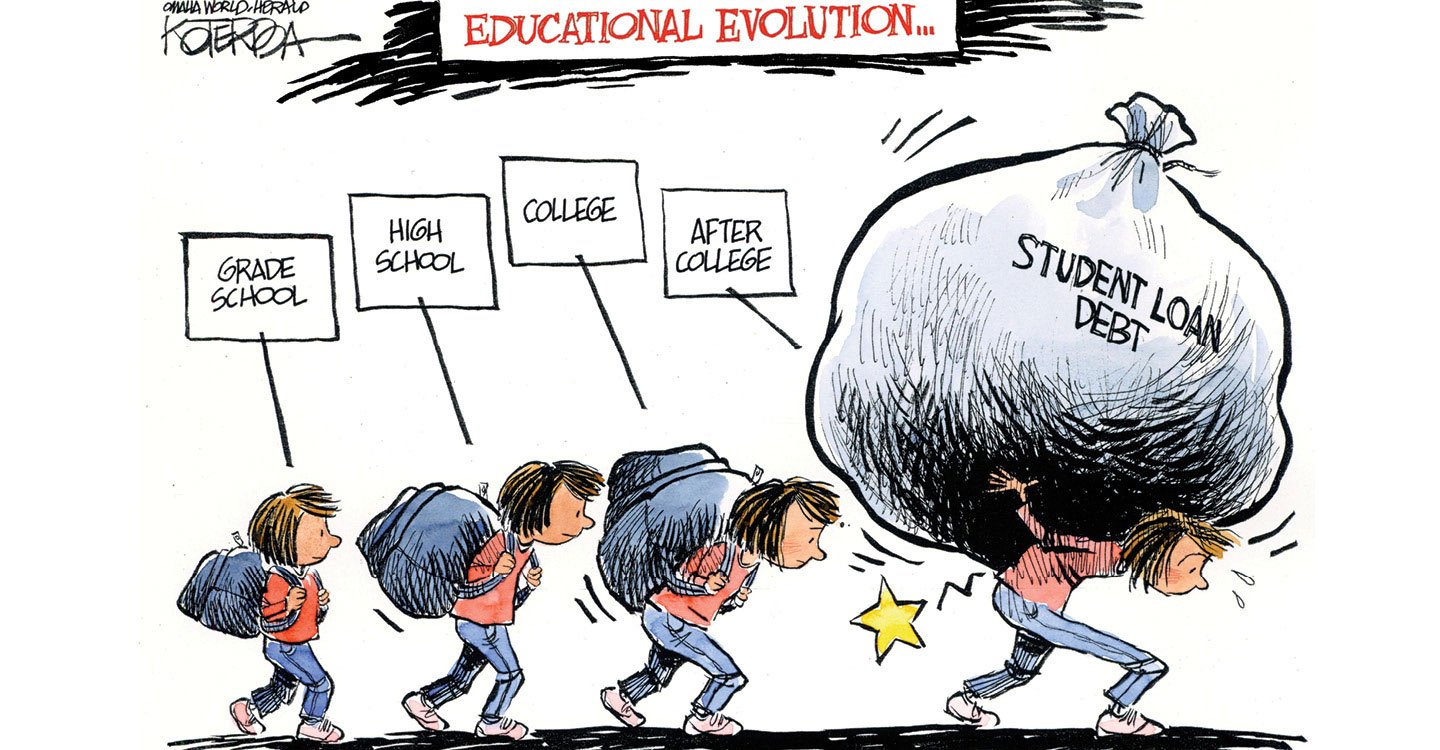

She’s far from the only college graduate saddled with debt. About two-thirds of seniors at four-year colleges are carrying student loans. In 2017, the average was more than $29,000, according to the Institute for College Access and Success, a nonprofit group advocating affordable higher education. That’s up from $13,000 in 1996, when adjusting for inflation.

“This generation of students is the most debt burdened ever, and it’s a huge problem for them,” says Mehrsa Baradaran, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, who specializes in banking law. “I do think you’re going to have a generation of students whose main concern, instead of finding a partner they love and coming up with a career, they have this huge part of their psychological and emotional toll being about the servicing of these debts.”

When she was a senior at High Point University in North Carolina, Brittany Gentilhomme began planning her future. She dreamed of renting an apartment and living on her own after graduation in 2017. Instead, she had difficulty landing a job in her chosen field, communications. That forced her to move back into her parents’ home in Milford, New Hampshire. She stayed with them for three years so she could try to make a dent in the $65,000 she borrowed in student loans. Gentilhomme, now 24, says living with her parents made her feel “like my life was on hold. I didn’t feel like an adult.”

She’s far from the only college graduate drowning in debt. About two-thirds of seniors at four-year colleges are carrying student loans. In 2017, the average amount was more than $29,000, according to the Institute for College Access and Success, a nonprofit group advocating affordable higher education. That’s up from $13,000 in 1996, when adjusting for inflation.

“This generation of students is the most debt burdened ever, and it’s a huge problem for them,” says Mehrsa Baradaran, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, who specializes in banking law. “I do think you’re going to have a generation of students whose main concern, instead of finding a partner they love and coming up with a career, they have this huge part of their psychological and emotional toll being about the servicing of these debts.”