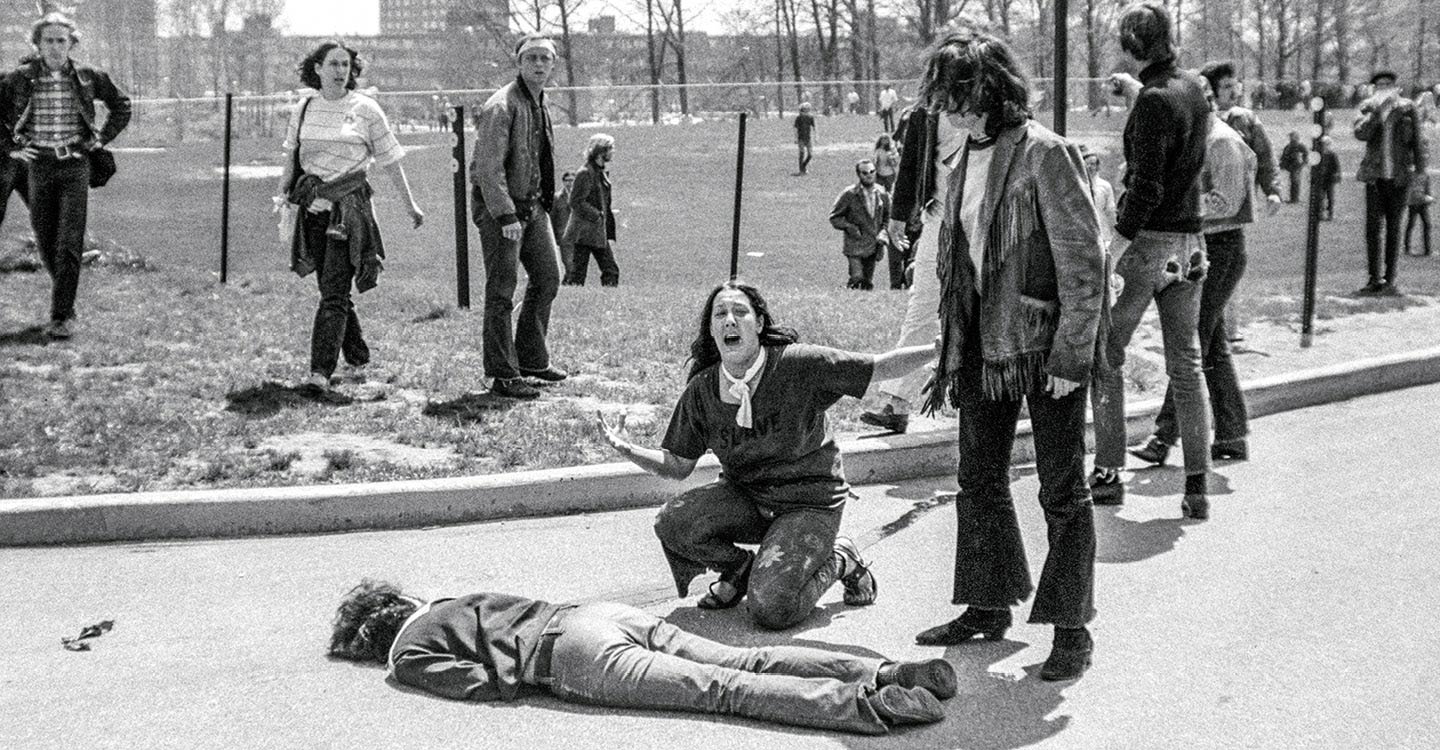

Dean Kahler heard bullets hit the ground around him as he lay facedown on the grass, his hands covering his head. He was a student at Kent State University in Ohio, and the Ohio National Guard, recently summoned to the campus, was shooting at him.

It was May 4, 1970. A few days earlier, guard troops had come to restore order after someone had set fire to the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (R.O.T.C.) building. Student activists were protesting the Vietnam War, spurred by President Richard Nixon’s recent announcement that he was expanding the conflict into Cambodia.

Kahler, an Ohioan only days past his 20th birthday, was just a curious bystander that afternoon. He had walked over to the campus Commons to observe the protests after class when suddenly the National Guard soldiers fired their M-1 rifles into a dispersing crowd of unarmed students.

“I could hear the bullets go zuuuup! right into the ground. It was probably within inches of my ear,” Kahler, now 69, remembers. “It wasn’t just one or two shots, it was four or five shots—until I finally got hit.”

Dean Kahler heard bullets hit the ground around him as he lay facedown on the grass, his hands covering his head. He was a student at Kent State University in Ohio. The Ohio National Guard had recently been called to the campus. Now the guardsmen were shooting at him.

It was May 4, 1970. A few days earlier, guard troops had come to restore order after someone had set fire to the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (R.O.T.C.) building. Student activists were protesting the Vietnam War. The protest was a response to President Richard Nixon’s recent announcement that he was expanding the conflict into Cambodia.

Kahler, an Ohioan only days past his 20th birthday, was just a curious bystander that afternoon. He had walked over to the campus Commons to observe the protests after class. Then suddenly, the National Guard soldiers fired their M-1 rifles into a dispersing crowd of unarmed students.

“I could hear the bullets go zuuuup! right into the ground. It was probably within inches of my ear,” Kahler, now 69, remembers. “It wasn’t just one or two shots, it was four or five shots—until I finally got hit.”