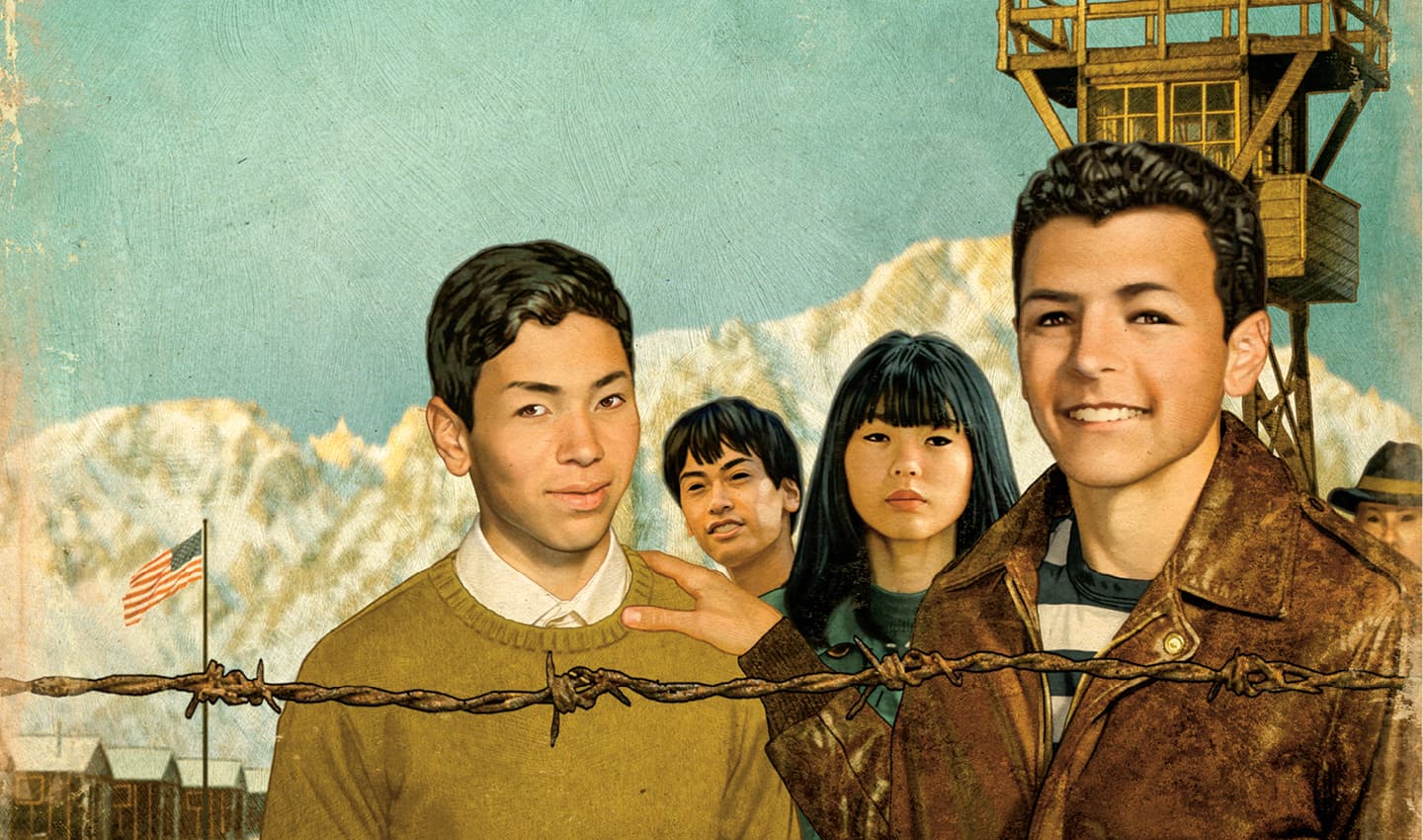

When Ralph Lazo, a high school student in Los Angeles, saw his Japanese American friends being forced from their homes and into internment camps during World War II, he did something unexpected: He went with them.

The United States government had set up the camps under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order to imprison Japanese Americans following Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii a few months earlier. From 1942 to 1946, more than 115,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the western U.S.—two-thirds of them American citizens and the rest legal immigrants—would be held in 10 camps, located in barren areas of the country.

In the spring of 1942, after seeing his classmates get sent away, 17-year-old

Ralph boarded a train and headed to the Manzanar Relocation Center, an internment camp in eastern California. Unlike the other inmates, Ralph didn’t have to be there. A Mexican American, he was the only known person to pretend to be Japanese so he could be willingly incarcerated.

What compelled Ralph to give up his freedom for two and a half years—sleeping in tar-paper-covered barracks, using open latrines and showers, and waiting on long lines for meals in mess halls, on grounds surrounded by barbed-wire fencing and watched by guards in towers? He wanted to be with his friends.

“My Japanese American friends at high school were ordered to evacuate the West Coast,” Ralph told the Los Angeles Times in 1944, “so I decided to go along with them.”

When Ralph Lazo, a high school student in Los Angeles, saw his Japanese American friends being forced from their homes and into internment camps during World War II, he did something unexpected: He went with them.

The United States government had set up the camps under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order to imprison Japanese Americans following Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii a few months earlier. From 1942 to 1946, more than 115,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in the western U.S.—two-thirds of them American citizens and the rest legal immigrants—would be held in 10 camps, located in barren areas of the country.

In the spring of 1942, after seeing his classmates get sent away, 17-year-old

Ralph boarded a train and headed to the Manzanar Relocation Center, an internment camp in eastern California. Unlike the other inmates, Ralph didn’t have to be there. A Mexican American, he was the only known person to pretend to be Japanese so he could be willingly incarcerated.

What compelled Ralph to give up his freedom for two and a half years—sleeping in tar-paper-covered barracks, using open latrines and showers, and waiting on long lines for meals in mess halls, on grounds surrounded by barbed-wire fencing and watched by guards in towers? He wanted to be with his friends.

“My Japanese American friends at high school were ordered to evacuate the West Coast,” Ralph told the Los Angeles Times in 1944, “so I decided to go along with them.”