Before its current term ends in June, the Supreme Court will have the potential to reshape U.S. law—and American life—on a host of hot-button issues. Cases on the docket include important ones about immigration, gun rights, gay rights, and jury trials. Adding to the potential drama: The rulings are expected early next summer, just as the presidential election will be heating up.

“Although the Court will carry on with a sense of normalcy,” says Lisa S. Blatt, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who often argues cases there, “it will be hard for them to ignore the polarization in the country.”

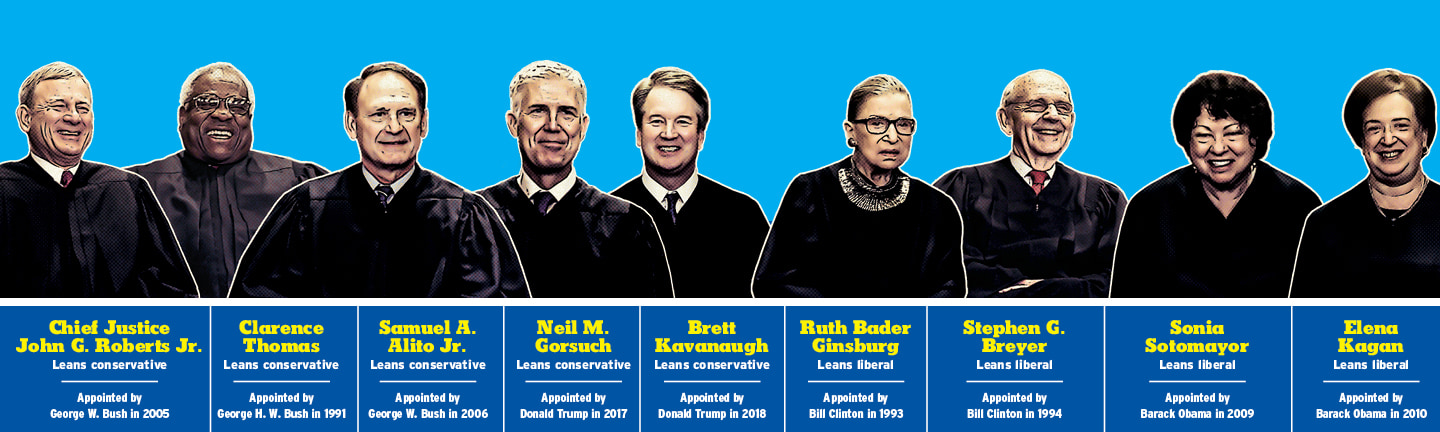

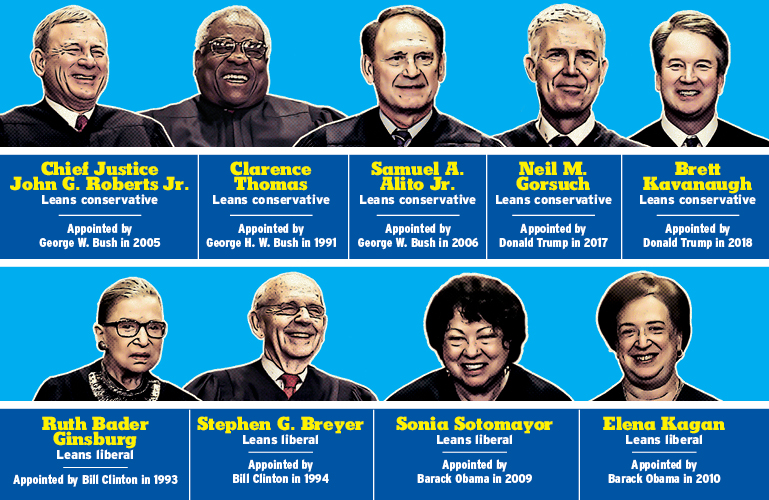

The Court’s newest member, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, took his seat last fall and cemented what is now a solid conservative majority. Kavanaugh, appointed by President Trump, replaced Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was often a swing vote between the Court’s liberal and conservative wings. Experts say Chief Justice John Roberts could be the new swing vote. Here’s what you need to know to understand some of the key cases.

Before its current term ends in June, the Supreme Court will have the potential to reshape U.S. law—and American life—on a host of hot-button issues. Cases on the docket include important ones about immigration, gun rights, gay rights, and jury trials. Adding to the potential drama: The rulings are expected early next summer, just as the presidential election will be heating up.

“Although the Court will carry on with a sense of normalcy,” says Lisa S. Blatt, a Washington, D.C., lawyer who often argues cases there, “it will be hard for them to ignore the polarization in the country.”

The Court’s newest member, Justice Brett Kavanaugh, took his seat last fall and cemented what is now a solid conservative majority. Kavanaugh, appointed by President Trump, replaced Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was often a swing vote between the Court’s liberal and conservative wings. Experts say Chief Justice John Roberts could be the new swing vote. Here’s what you need to know to understand some of the key cases.