Jim McMahon

When Calvin Ong was 10 years old, he said goodbye to his mother, brother, and friends in China to move to a land where he didn’t speak the language and knew almost no one: the United States.

It was the summer of 1937, and to get to his new home, Ong had to spend 18 days at sea on a crowded ship, sharing a room and bathroom with four strangers. He planned to start a new life with his father, who had already moved to California and become a U.S. citizen.

“America was a land of opportunity,” says Ong, now 93. “I could seek an education, find a job, and earn money to improve my family’s situation.”

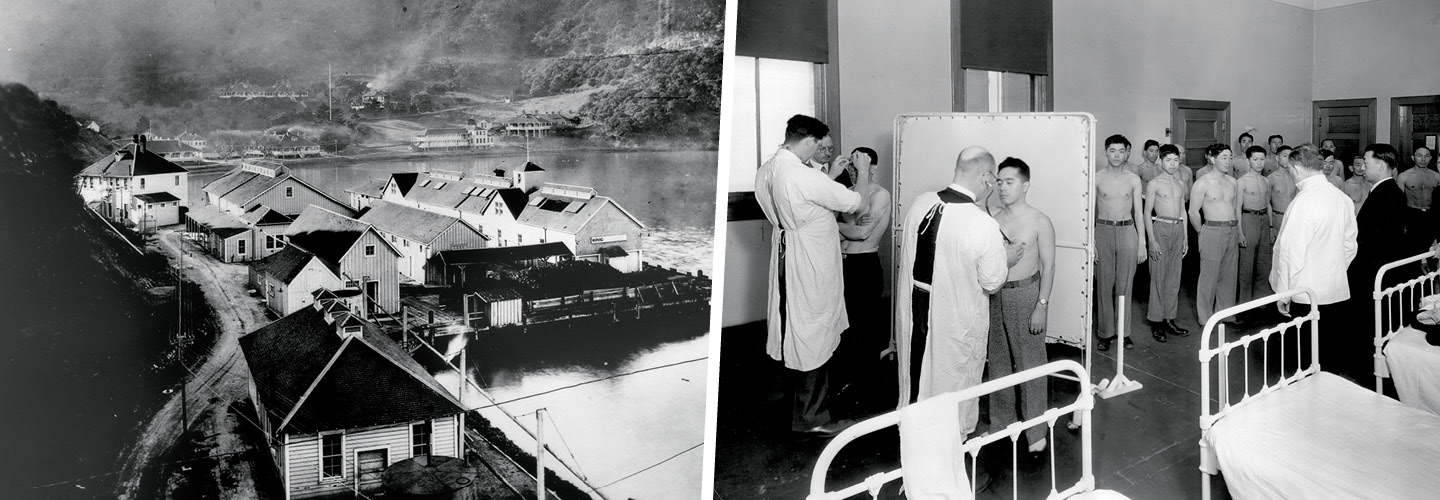

But he soon found out that the American dream wouldn’t be easy to achieve. His first stop in the U.S. was Angel Island, an immigration station near San Francisco. It was built primarily to keep out immigrants from Asia, not welcome them.

You probably know about Ellis Island, the immigration station in New York Harbor, which processed and admitted more than 12 million immigrants from 1892 to 1954—most of them from Europe. It stands today, along with the Statue of Liberty nearby, as a symbol of America’s long history of opening its doors to immigrants (see timeline slideshow, below).

But Angel Island, located on the other side of the country, tells a different—more complicated—story about immigration in the U.S. Today, with violence against Asian American and Pacific Islander communities escalating during the pandemic (see “Battling Hate,” below), Edward Tepporn, executive director of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, says it’s important to understand this immigration story too.

“What Angel Island reminds us is that the U.S. has not always been completely welcoming of immigrants,” says Tepporn, “and has taken active effort to exclude certain immigrant groups.”

When Calvin Ong was 10 years old, he said goodbye to his mother, brother, and friends in China. He was preparing to move to a land where he didn’t speak the language and knew almost no one: the United States.

It was the summer of 1937. To get to his new home, Ong had to spend 18 days at sea on a crowded ship, sharing a room and bathroom with four strangers. His father had already moved to California. Ong planned to start a new life with him and become a U.S. citizen.

“America was a land of opportunity,” says Ong, now 93. “I could seek an education, find a job, and earn money to improve my family’s situation.”

But he soon found out that the American dream wouldn’t be easy to achieve. His first stop in the U.S. was Angel Island, an immigration station near San Francisco. It was built primarily to keep out immigrants from Asia, not welcome them.

You probably know about Ellis Island, the immigration station in New York Harbor. That station processed and admitted more than 12 million immigrants from 1892 to 1954. Most of them came from Europe. It stands today, along with the Statue of Liberty nearby, as a symbol of America’s long history of opening its doors to immigrants (see timeline slideshow, below).

But Angel Island, located on the other side of the country, tells a different story about immigration in the U.S. And it’s a more complicated story. Today, violence against Asian American and Pacific Islander communities has escalated during the pandemic (see “Battling Hate,” below). Edward Tepporn, executive director of the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation, says that’s why it’s important to understand this immigration story too.

“What Angel Island reminds us is that the U.S. has not always been completely welcoming of immigrants,” says Tepporn, “and has taken active effort to exclude certain immigrant groups.”