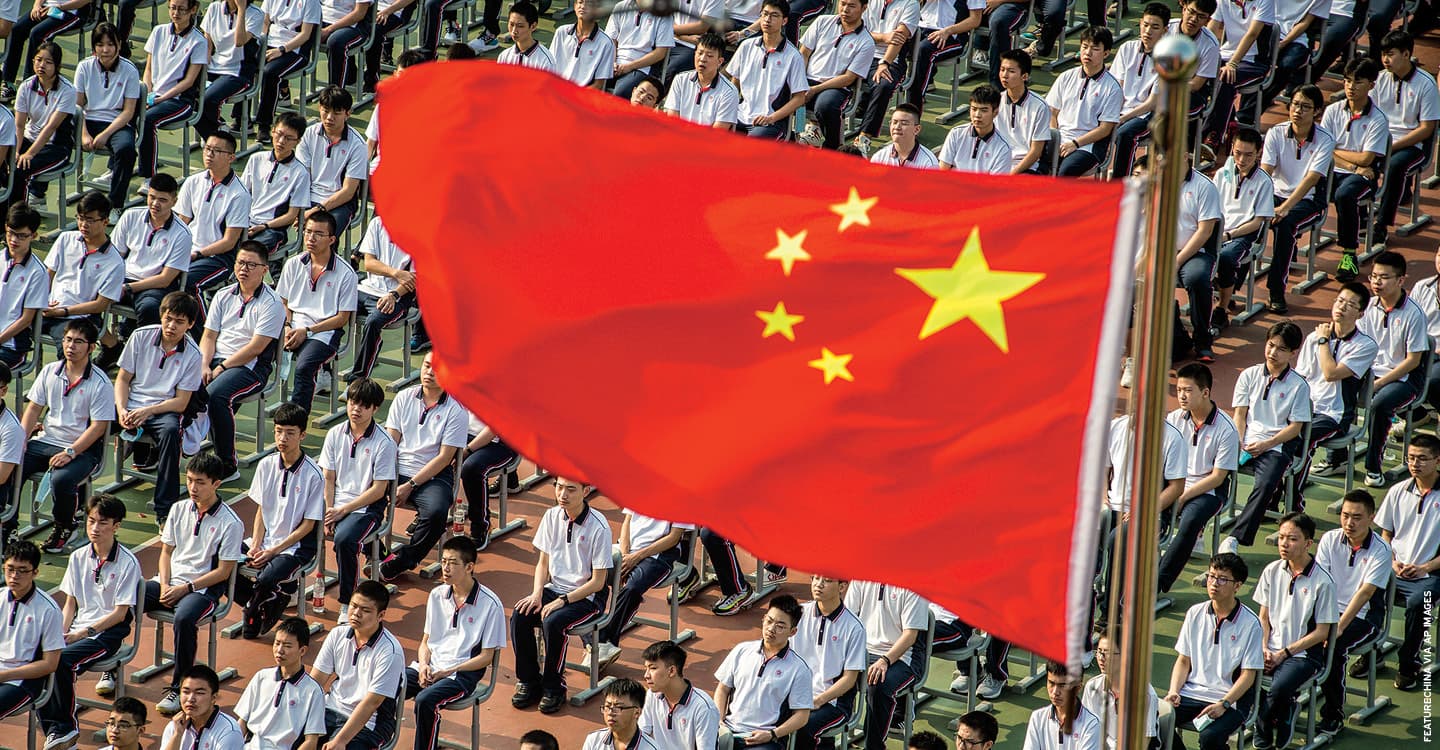

On a sunny day in September, nearly 2,000 students gathered for the start of school at Hanyang No. 1 High School in Wuhan, the Chinese city where the coronavirus first emerged late last year.

Medical staff stood guard at school entrances, taking temperatures. Administrators reviewed the students’ travel histories and Covid test results. Local Communist Party officials kept watch, making sure teachers followed detailed instructions on hygiene and showed an “anti-epidemic spirit.”

“I’m not worried,” said Yang Meng, a music teacher at the school. “Wuhan is now the safest place.”

As many parts of the U.S. have struggled to reopen schools amid the pandemic, China has harnessed the power of its authoritarian system to offer in-person learning for about 195 million students in kindergarten through 12th grade at public schools.

China is a Communist country, and it has used the government’s vise-like control to implement a rigid system for opening all the nation’s schools. The Communist Party has mobilized battalions of local officials to inspect classrooms, deployed apps and other technology to monitor students and staff, and restricted their movements in ways that would be impossible in the U.S. It has even told parents to stay away for fear of spreading germs.

On a sunny day in September, nearly 2,000 students gathered for the start of school at Hanyang No. 1 High School in Wuhan, the Chinese city where the coronavirus first emerged late last year.

Medical staff stood guard at school entrances, taking temperatures. Administrators looked over the students’ travel histories and Covid test results. Local Communist Party officials kept watch. They ensured teachers followed detailed instructions on hygiene and showed an “anti-epidemic spirit.”

“I’m not worried,” said Yang Meng, a music teacher at the school. “Wuhan is now the safest place.”

Many parts of the U.S. have struggled to reopen schools during the pandemic. Things in China are quite different. The country has used its authoritarian system’s power to offer in-person learning. Its public schools serve about 195 million students in kindergarten through 12th grade.

China is a Communist country. It has used its government’s control to put in place a rigid system for opening all the nation’s schools. The Communist Party has mobilized units of local officials to inspect classrooms. And it’s released apps and other technology to watch students and staff. In fact, their movements have been limited in ways that would be impossible in the U.S. It has even told parents to stay away for fear of spreading germs.