The Supreme Court is in the midst of what appears to be another blockbuster term. The nation’s highest court will tackle cases involving social media, affirmative action, voting rights, election laws, and how to balance religious freedom with antidiscrimination laws—all hot-button issues that could change the contours of American life depending on how the Court rules.

“The cases the Court will hear have great potential to be very significant,” says Jeffrey Fisher, a law professor at Stanford University. “But you never know until the Court issues an opinion whether the Court will do big things or not.”

This term’s high-stakes docket comes on the heels of a series of high-profile rulings last June. The Court reversed its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which had established a constitutional right to abortion; said Americans have a constitutional right to carry guns outside the home; and restricted the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate carbon emissions from power plants, which had been part of the Biden administration’s plan to address climate change.

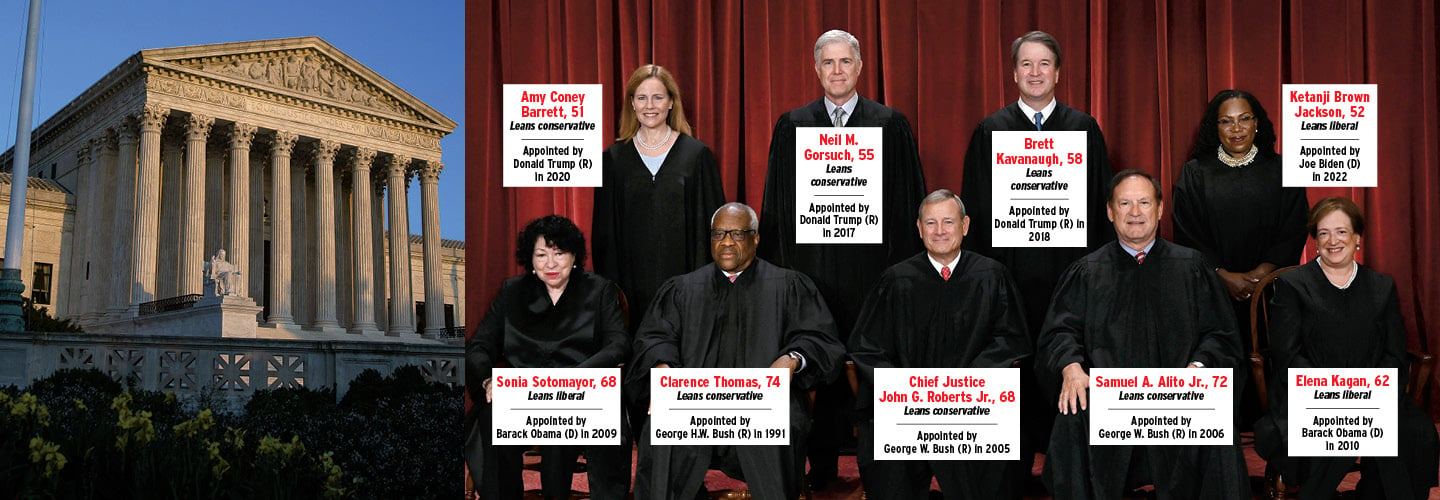

Six conservative-leaning justices now control the nine-member Court, and they seem poised to dominate this year’s decisions as they did last year’s. The Court does have a new justice this year, Ketanji Brown Jackson, who is the first African American woman to serve on the Court. But her appointment doesn’t change the balance of power, since she’s expected to be liberal-leaning, like her predecessor, Stephen Breyer.

“On things that matter most,” says Irv Gornstein, the executive director of the Supreme Court Institute at Georgetown University Law Center, “get ready for a lot of 6-3s”—meaning 6-to-3 rulings.

Here’s a look at five of the most important issues the Court is considering.

The Supreme Court is in the middle of what appears to be another blockbuster term. The nation’s highest court will tackle cases involving social media, affirmative action, voting rights, election laws, and how to balance religious freedom with antidiscrimination laws. How the Court rules on these hot-button issues could change the fabric of American life.

“The cases the Court will hear have great potential to be very significant,” says Jeffrey Fisher, a law professor at Stanford University. “But you never know until the Court issues an opinion whether the Court will do big things or not.”

This term’s high-stakes docket comes on the heels of a series of high-profile rulings last June. The Court reversed its 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which had established a constitutional right to abortion. It also said that Americans have a constitutional right to carry guns outside the home. And it restricted the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate carbon emissions from power plants. The tactic had been part of the Biden administration’s plan to address climate change.

Six conservative-leaning justices now control the nine-member Court. This group will likely dominate this year’s decisions as they did last year’s. The Court does have a new justice this year, Ketanji Brown Jackson. She is the first African American woman to serve on the Court. Like Stephen Breyer, the justice who held her seat before her, she’s expected to be liberal-leaning. So, her appointment doesn’t change the balance of power.

“On things that matter most,” says Irv Gornstein, the executive director of the Supreme Court Institute at Georgetown University Law Center, “get ready for a lot of 6-3s”—meaning 6-to-3 rulings.

Here’s a look at five of the most important issues the Court is considering.