Last year, Edward Thomas, now 17, quit social media entirely.

It wasn’t an easy decision, especially since most of his friends use social media to message each other. But the Chicago teen worried about online companies tracking his activities and using that information to either make money or influence the kind of content shown in his feeds.

“Social media and other Big Tech companies have no legal obligation to share how they use our consumer behavior, like how much time we spend on TikTok and what we like,” Edward says. “For all I know, they could be scanning through messages I’m sending my friends.”

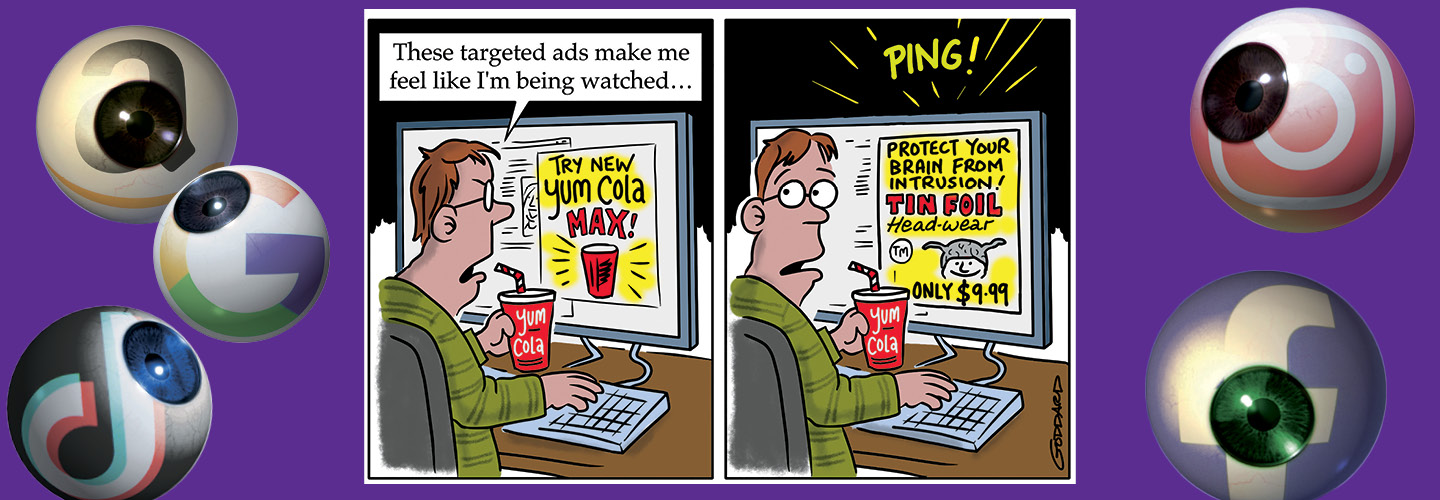

Many privacy experts say Edward is right to be concerned. Internet giants such as Facebook and Google have long tracked people’s internet browsing, studying their habits and using that information for advertising (see “What They Do With Your Data,” below). If, say, someone were to scroll through Instagram and then click on a website selling shoes, marketers might start targeting that person with footwear ads. It’s a big business: The digital ad industry was worth $522.5 billion in 2021 and is growing rapidly. Smartphones have made it even easier to track people’s data, including their locations and health details.

You might be surprised by how much social media companies know about you. Maybe you’ve entered your birthday and gender into your profile, and you follow a few influencers or brands. But companies can uncover a lot more than what you’ve told them, privacy experts say. These platforms can look at your friends, online activity, location, and more. They can then put together a detailed picture of who they think you are. Much of that is information you may never have disclosed, such as your political beliefs, your mental and physical health, and who lives with you. Some platforms can even use credit card numbers to monitor your offline purchases.

Edward Thomas, now 17, quit using social media last year.

It wasn’t an easy decision. It was difficult because most of his friends use social media to message each other. But the Chicago teen worried about online companies tracking his activities. He worried they were using that information to either make money or influence the kind of content shown in his feeds.

“Social media and other Big Tech companies have no legal obligation to share how they use our consumer behavior, like how much time we spend on TikTok and what we like,” Edward says. “For all I know, they could be scanning through messages I’m sending my friends.”

Many privacy experts say Edward is right to be concerned. Internet giants such as Facebook and Google have long tracked people’s internet browsing. They study user habits and use that information for advertising (see “What They Do With Your Data,” below). If someone were to scroll through Instagram and then click on a website selling shoes, marketers might start targeting that person with footwear ads. It’s a big business. The digital ad industry was worth $522.5 billion in 2021. It is growing rapidly. Smartphones have made it even easier to track people’s data, including their locations and health details.

You might be surprised by how much social media companies know about you. Maybe you’ve entered your birthday and gender into your profile. Then you follow a few influencers or brands. But companies can uncover a lot more than what you’ve told them, privacy experts say. These platforms can look at your friends. They can track your online activity, location, and more. They can then put together a detailed picture of who they think you are. Much of that is information you may never have disclosed. But they can learn about your political beliefs, your mental and physical health, and who lives with you. Some platforms can even use credit card numbers to monitor your offline purchases.