The United States was a mess. It was 1787, and the young nation was deep in debt, the 13 states refused to work together—and there was no central leader to do anything about it.

How did it happen? Historians blame the first U.S. constitution—the Articles of Confederation—which the Continental Congress had adopted 10 years earlier, in 1777. That constitution initially gave almost all power to the individual states—making the central government so weak that it couldn’t even enforce laws.

But there was hope. Delegates from the states gathered in Pennsylvania in May 1787 to find a solution. Some said the Articles could be fixed, while others wanted to start over and create a new document that laid out the laws of the nation.

After months of heated debate, the men (no women were invited) wrote a new Constitution that set up a strong federal government. Using a quill pen, a majority of the delegates signed it. The document couldn’t take effect, however, without nine of the states ratifying it. Each state held its own special convention to decide.

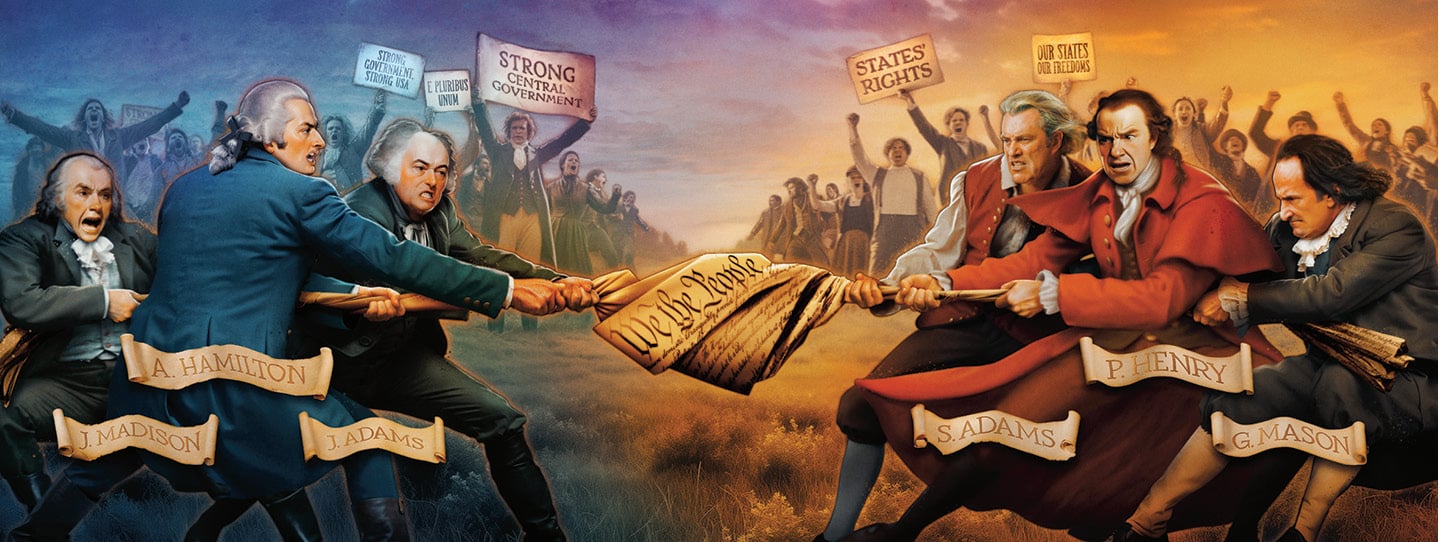

Quickly, two groups emerged, with very different ideas about the role of the U.S. government: The Federalists liked the new Constitution because it gave the federal government a lot of power. The Antifederalists didn’t. They thought Americans’ freedoms were better protected by state governments. During the era of the constitutional clash, both sides gave speeches and published essays to persuade the states.

The fights sometimes turned violent. In the summer of 1788, Federalists staged a march through Albany, New York. A group of Antifederalists confronted them. An account printed in Freeman’s Journal said “a general battle took place, with swords, bayonets, clubs, stones . . . which lasted for some time, both parties fighting with the greatest rage.”

Many of the disagreements that surfaced when the nation was in its infancy are still going on today.

“We were having these fights 250 years ago, and these fights weren’t resolved by the U.S. Constitution,” says Henry L. Chambers Jr., a law professor at the University of Richmond in Virginia.

The United States was a mess. It was 1787, and the young nation was deep in debt. The 13 states refused to work together. There was no central leader to do anything about it.

How did it happen? Historians blame the first U.S. constitution, called the Articles of Confederation. The Continental Congress had adopted it in 1777. That constitution initially gave almost all power to the individual states. It made the central government so weak that it couldn’t even enforce laws.

But there was hope. Delegates from the states gathered in Pennsylvania in May 1787 to find a solution. Some said the Articles could be fixed. Others wanted to start over and create a new document that laid out the laws of the nation.

After months of heated debate, the men (no women were invited) wrote a new Constitution that set up a strong federal government. Using a quill pen, a majority of the delegates signed it. However, the document couldn’t take effect. Nine of the states had to ratifying it. Each state held its own special convention to decide.

Quickly, two groups emerged. They had very different ideas about the role of the U.S. government. The Federalists liked the new Constitution because it gave the federal government a lot of power. The Antifederalists didn’t. They thought Americans’ freedoms were better protected by state governments. During the era of the constitutional clash, both sides gave speeches. They published essays to persuade the states.

The fights sometimes turned violent. In the summer of 1788, Federalists staged a march through Albany, New York. A group of Antifederalists confronted them. An account printed in Freeman’s Journal said, “a general battle took place, with swords, bayonets, clubs, stones . . . which lasted for some time, both parties fighting with the greatest rage.”

Many of the disagreements that surfaced then are still going on today.

“We were having these fights 250 years ago, and these fights weren’t resolved by the U.S. Constitution,” says Henry L. Chambers Jr., a law professor at the University of Richmond in Virginia.