Courtesy Janice Wesley Kelsey

Janice Wesley in 1965

Janice Wesley woke up on Thursday, May 2, 1963, “with my mind on freedom,” as she would later say. The 16-year-old put on a light, sleeveless dress: Even spring days can get hot in Birmingham, Alabama. Thinking ahead, she stuck a toothbrush and toothpaste into her purse, and grabbed her older sister’s leather jacket. It might be cold at night in jail.

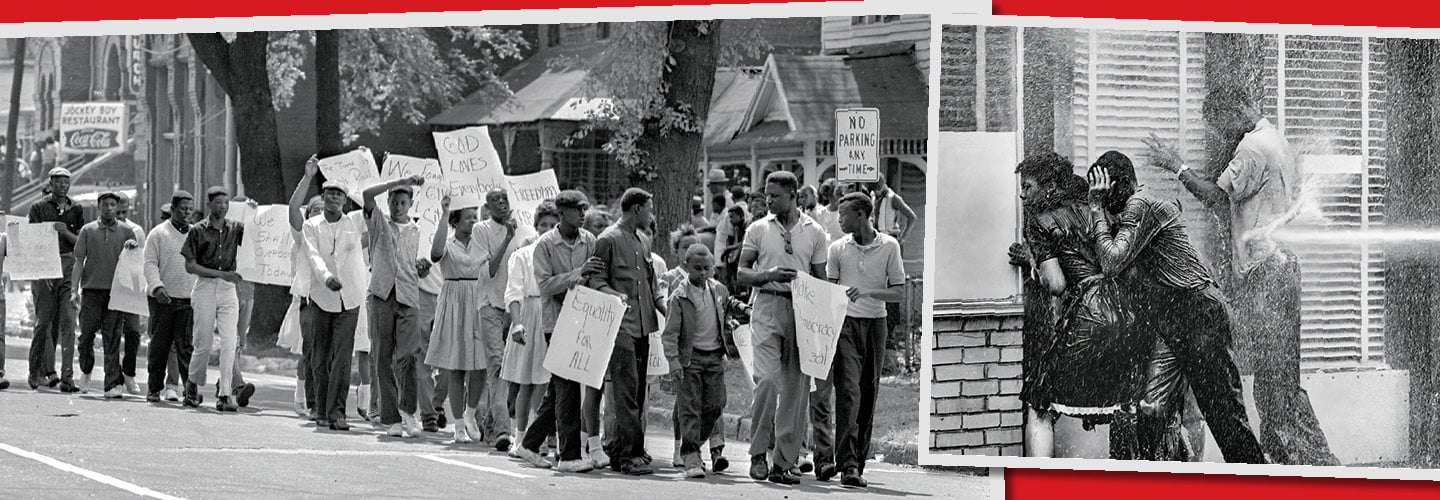

Janice was about to take part in a march to end segregation in Birmingham, then one of the most racially divided cities in the United States. The city had denied protest organizers, including Martin Luther King Jr., a permit to demonstrate, so they knew that many of those who marched were likely to be arrested.

At that time, the American civil rights movement was engaged in a historic struggle: to achieve equal rights for Black citizens after centuries of discrimination (see timeline slideshow, below). The protest that day in Birmingham, like many others before it, sought to integrate businesses that separated people by race. But one thing set this march apart: It would be largely made up of young people. In fact, most Black adults didn’t even know about it—including Janice’s parents. They would have been too worried to let their teenaged and even younger children take part.

Indeed, within the coming days, the young protesters would face violent opposition, and hundreds of them would be arrested. Yet their courage in what has become known as the Children’s Crusade would change the city—and the nation—in ways few Americans could have foreseen.

Janice Wesley woke up on Thursday, May 2, 1963, “with my mind on freedom,” as she would later say. The 16-year-old put on a light, sleeveless dress. Spring days can get hot in Birmingham, Alabama. She stuck a toothbrush and toothpaste into her purse. She grabbed her older sister’s leather jacket. It might be cold at night in jail.

Janice was about to take part in a march to end segregation in Birmingham. It was one of the most racially divided cities in the United States. The city had denied protest organizers, including Martin Luther King Jr., a permit to demonstrate. So organizers knew that many of those who marched were likely to be arrested.

At that time, the American civil rights movement was engaged in a historic struggle. The goal was to achieve equal rights for Black citizens after centuries of discrimination (see timeline slideshow, below). The protest that day in Birmingham sought to integrate businesses that separated people by race. But this march was different. It would be largely made up of young people. In fact, most Black adults didn’t even know about it—including Janice’s parents. They would have been too worried to let their teenaged and even younger children take part.

Indeed, within the coming days, the young protesters would face violent opposition. Hundreds of them would be arrested. Yet their courage in what has become known as the Children’s Crusade would change the city—and the nation—in ways few Americans could have foreseen.