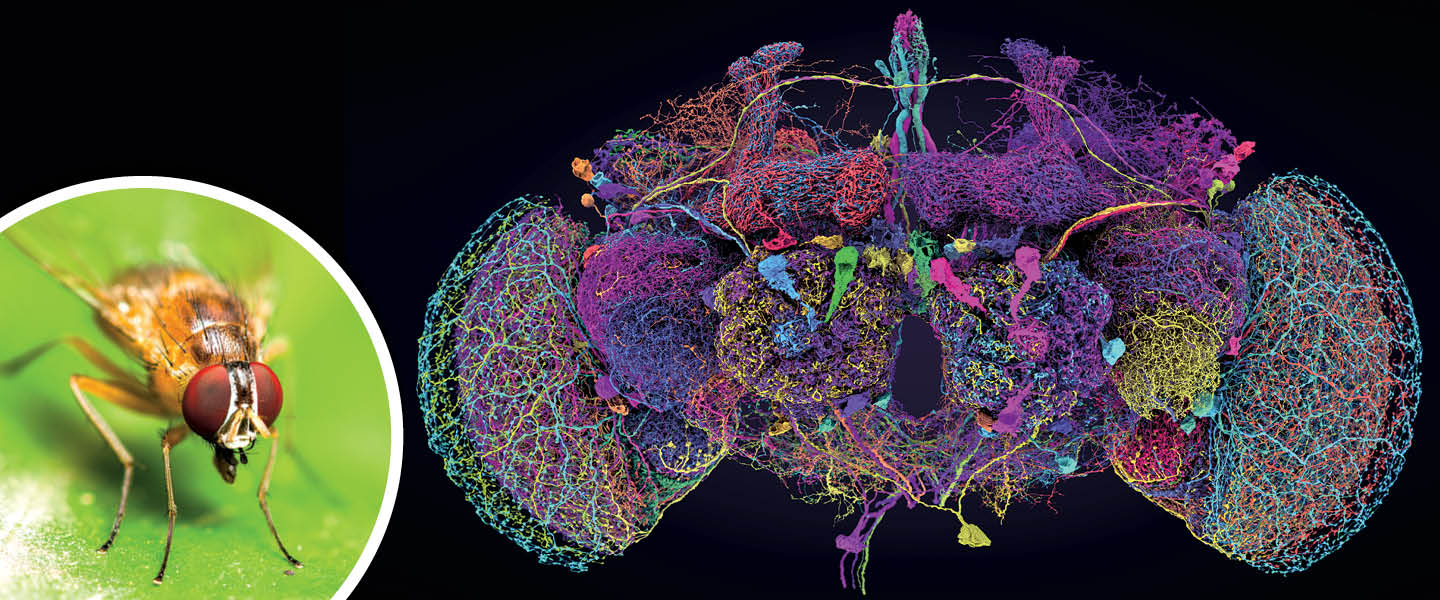

The fruit fly’s brain is smaller than a poppy seed, but there’s tremendous complexity in that tiny space. This map of the fruit fly brain—which took hundreds of scientists more than a decade to create—shows more than 140,000 neurons joined together by about 490 feet of wiring. (Neurons are nerve cells that send messages through the body and allow it to do everything from breathe to eat.) It’s the first complete map of any complex brain. The project began in 2013, when researchers in Virginia dunked the brain of an adult fruit fly in a chemical bath, hardening it into a solid block. They shaved an exquisitely thin layer off the top and used a microscope to take pictures. Then they shaved another layer and took a new picture; to capture the entire brain, they imaged 7,050 sections and produced 21 million pictures. Now they hope to use the fruit fly map to discover fundamental rules for more complex brains. Once scientists better understand the human brain—which has 86 billion neurons—they hope they might be able to cure brain diseases such as dementia, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s. “Just like you wouldn’t want to drive to a new place without Google Maps, you don’t want to explore the brain without a map,” says co-author Sven Dorkenwald of Princeton University. “With this, researchers are now equipped to thoughtfully navigate the brain as we try to understand it.”

A complex map: The different colors represent distinct circuits of neurons that run throughout a fruit fly’s brain. Tyler Sloan and Amy Sterling for FlyWire at Princeton University (brain); Alongkot Sumritjearapol/Getty Images (fly)

Text-to-Speech