Ricardo Martinez was in his high school lunchroom last April when a massive brawl erupted.

He watched, horrified, as a dozen teenage boys rampaged through the cafeteria, pummeling and kicking one another, overturning tables and chairs. Other students jeered and jostled to film the fight on their phones.

“It was like a stampede of videos,” says Ricardo, now 18 and a senior. “Everyone was trying to get the best angle.”

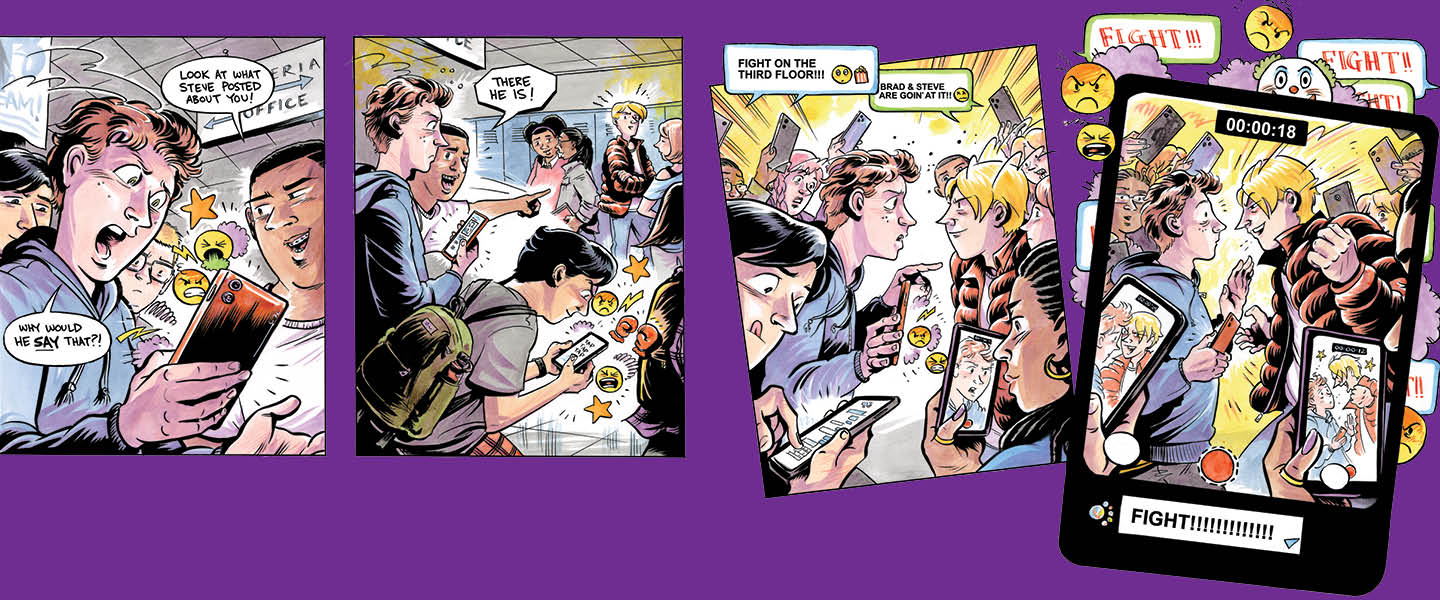

But the pandemonium at Revere High School in Revere, Massachusetts, was just beginning. Within minutes, students in other parts of the building began receiving text messages about the lunchroom brawl. Suddenly, teachers said, dozens of riled-up teenagers started racing down hallways and careening down stairways with their phones to get to the fight.

To stop more people from flooding into the cafeteria, Revere High posted staff members in front of the lunchroom entrances and issued a “hold” order to keep students in their classrooms. Administrators called the police to help restore calm. The school said it ultimately suspended 17 students involved in the brawl.

Across the United States, smartphone technology has increasingly fueled and sometimes intensified campus brawls, disrupting schools and derailing learning. The school fight videos often spark new cycles of student cyberbullying, verbal aggression, and violence.

A New York Times investigation into the problem in more than a dozen states, including Massachusetts, California, Georgia, and Texas, found a pattern of middle and high school students exploiting phones and social media to arrange, provoke, capture, and spread footage of brutal beatings among their peers. In several cases, students later died from the injuries.

Ricardo Martinez was in his high school lunchroom last April when a big fight broke out.

He watched, horrified. A dozen teenage boys raged through the cafeteria, hitting and kicking one another. Tables and chairs were overturned. Other students jeered and tried to film the fight on their phones.

“It was like a stampede of videos,” says Ricardo, now 18 and a senior. “Everyone was trying to get the best angle.”

But the chaos at Revere High School in Revere, Massachusetts, was just beginning. Within minutes, students in other parts of the building began receiving text messages about the fight. Suddenly dozens of excited teenagers started racing down hallways and running down stairways with their phones to film the fight.

To stop more people from entering the cafeteria, Revere High posted staff members in front of the lunchroom entrances. They issued a “hold” order to keep students in their classrooms. Administrators called the police to help restore calm. The school said 17 students involved in the fight were suspended.

Across the United States, smartphone technology has increased and, sometimes, intensified campus brawls. These fights disrupt school and learning. The school fight videos often spark new cycles of student cyberbullying, verbal aggression, and violence.

The New York Times investigated the problem in more than a dozen states, including Massachusetts, California, Georgia, and Texas. The investigation found a pattern of middle and high school students exploiting phones and social media to arrange and provoke fights. The footage of brutal beatings among students was then captured and shared. In several cases, students later died from the injuries.