Young women hunch over sewing machines in a windowless workroom in Bangladesh. Elbow to elbow in the stifling heat, they assemble jackets. Together, the women must sew hundreds of jackets an hour, more than 1,000 a day. Their daily wage is less than $3.

Just a week or two later, these same jackets will be labeled fall’s hottest back-to-school item, selling to teens for $14.99 each at malls across the United States.

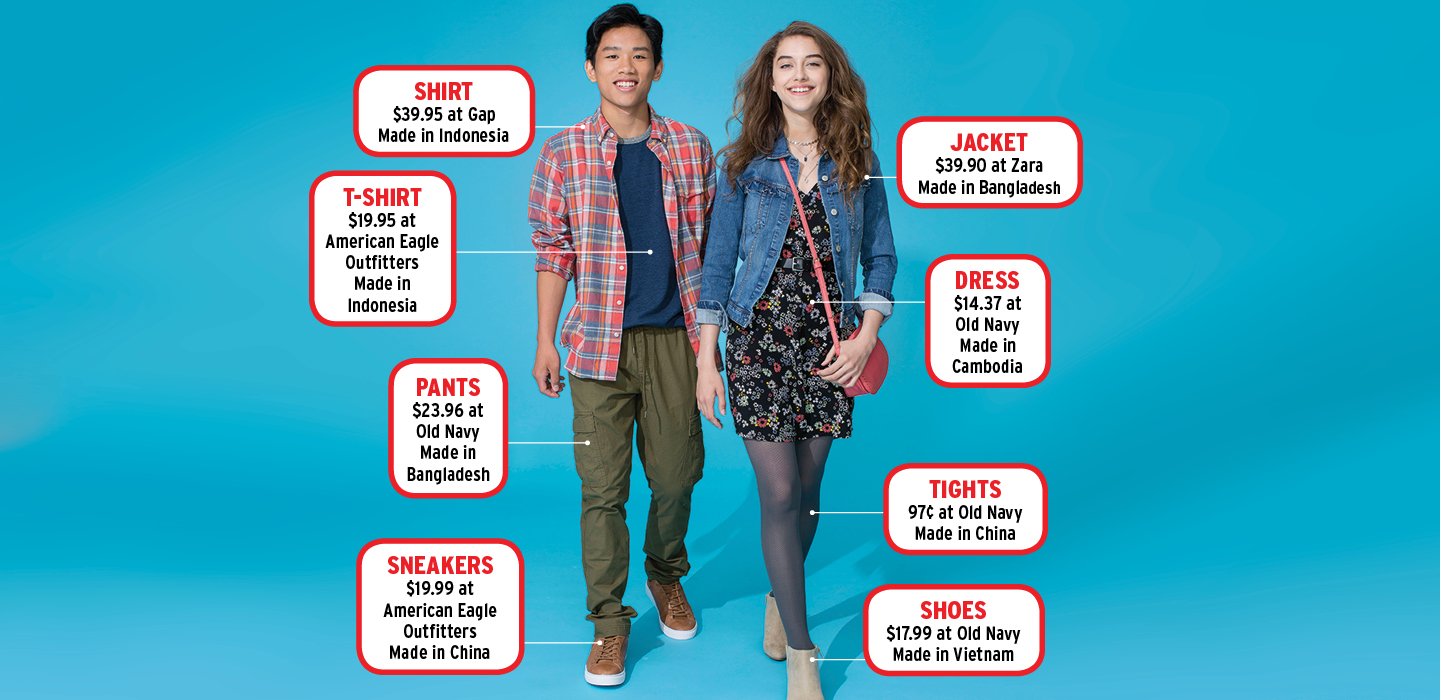

The jackets are just one example of what is known as fast fashion: trendy clothes designed, created, and sold to consumers as quickly as possible at extremely low prices. New looks arrive in stores weekly or even daily, and they cost so little that many people can afford to fill their closets with new outfits multiple times each year—then toss them the minute they go out of style.

Chains such as H&M and Zara first popularized fast fashion in the early 2000s. It has since spread throughout the entire clothing industry. As a result, global clothing production has more than tripled since 2000. The industry now churns out more than 150 billion garments annually.

Young women hunch over sewing machines in a windowless workroom in Bangladesh. Elbow to elbow in the stifling heat, they assemble jackets. Together, the women must sew hundreds of jackets an hour. That's more than 1,000 a day. Their daily wage is less than $3.

Just a week or two later, these same jackets will be labeled fall’s hottest back-to-school item. Teens will buy them for $14.99 each at malls across the United States.

The jackets are just one example of what is known as fast fashion. This refers to trendy clothes designed, created, and sold to consumers as quickly as possible at extremely low prices. New looks arrive in stores weekly or even daily. They cost so little that many people can afford to fill their closets with new outfits throughout the year. They’re then tossed out the minute they go out of style.

Chains such as H&M and Zara first popularized fast fashion in the early 2000s. It has since spread throughout the entire clothing industry. As a result, global clothing production has more than tripled since 2000. The industry now churns out more than 150 billion garments a year.