Lately, it seems as if the federal government is at war with itself. The House of Representatives has been investigating the White House, and lawmakers have threatened to impeach President Trump over the findings in the Mueller Report. Earlier in the year, the president vetoed a congressional resolution that would have prevented him from building his wall on the U.S.-Mexico border without Congress’s approval. And a battle over one of Trump’s appointees to the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh, was among the nastiest in memory.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has gone so far as to say that the nation is mired in a “constitutional crisis” over the president’s blanket refusal to cooperate with congressional investigations. Trump has responded by vowing not to work with Democrats in Congress on any legislation until the investigations end.

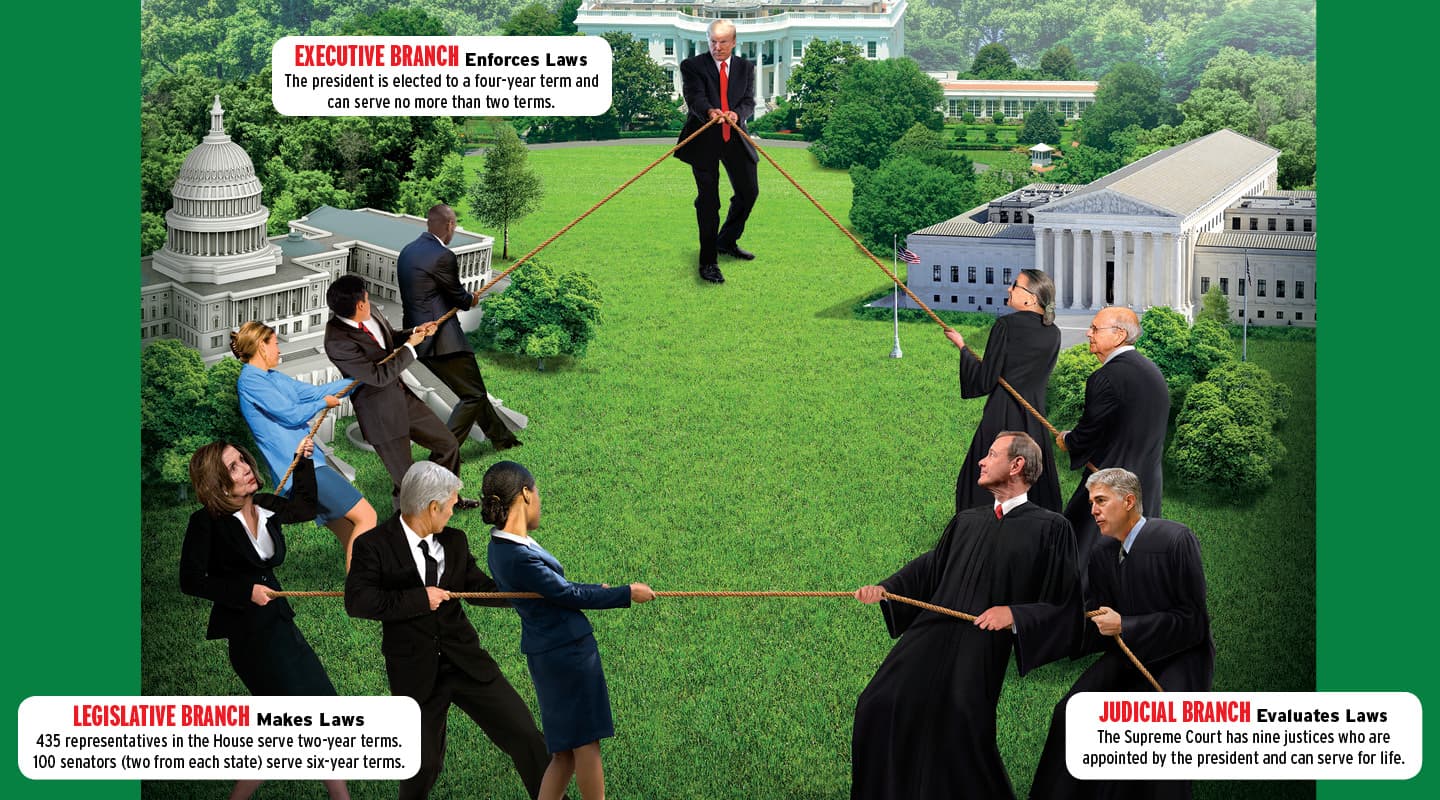

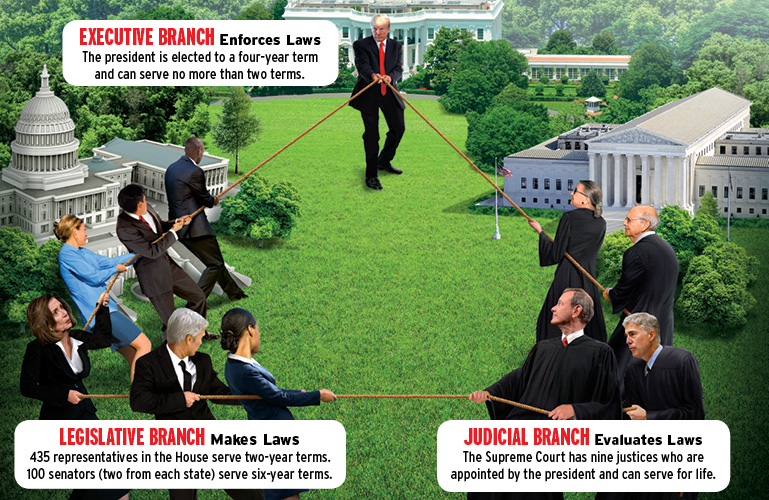

What’s going on? Experts say it’s a particularly heated showdown involving America’s system of checks and balances. The Framers spread power among the three federal branches—executive, legislative, and judicial—and gave each branch the ability to curb, or check, the power of the other two. In many cases, the system works without much fuss, as when Congress approves a president’s Cabinet nominee. At other times in American history, two branches have dug in their heels and fought over their respective powers.

“We’ve had some challenges in the past, and the system responded appropriately,” says Norman Ornstein, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C. “But I think we’re at a time of enormous and important testing of the system.”

Here’s what you need to know about checks and balances, and how they might come into play in the year ahead.

Lately, it seems as if the federal government is at war with itself. The House of Representatives has been investigating the White House. Lawmakers have threatened to impeach President Trump over the findings in the Mueller Report. Earlier in the year,

the president vetoed a congressional resolution that would have prevented him from building his wall on the U.S.-Mexico border without Congress’s approval. And a battle over one of Trump’s appointees to the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanaugh, was among the nastiest in memory.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has gone so far as to say that the nation is mired in a “constitutional crisis” over the president’s blanket refusal to cooperate with congressional investigations. Trump has responded by vowing not to work with Democrats in Congress on any legislation until the investigations end.

What’s going on? Experts say it’s a particularly heated showdown. And it’s one that involves America’s system of checks and balances. The Framers spread power among the three federal branches—executive, legislative, and judicial. They gave each branch the ability to curb, or check, the power of the other two. In many cases, the system works without much fuss. An example is when Congress approves a president’s Cabinet nominee. At other times in American history, two branches have dug in their heels and fought over their respective powers.

“We’ve had some challenges in the past, and the system responded appropriately,” says Norman Ornstein, a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington, D.C. “But I think we’re at a time of enormous and important testing of the system.”

Here’s what you need to know about checks and balances, and how they might come into play in the year ahead.