TikTok is quietly becoming a political force all over the world. In the United States, plenty of people—especially teens—increasingly rely on the platform for election information, news updates, and fact-checking commentary.

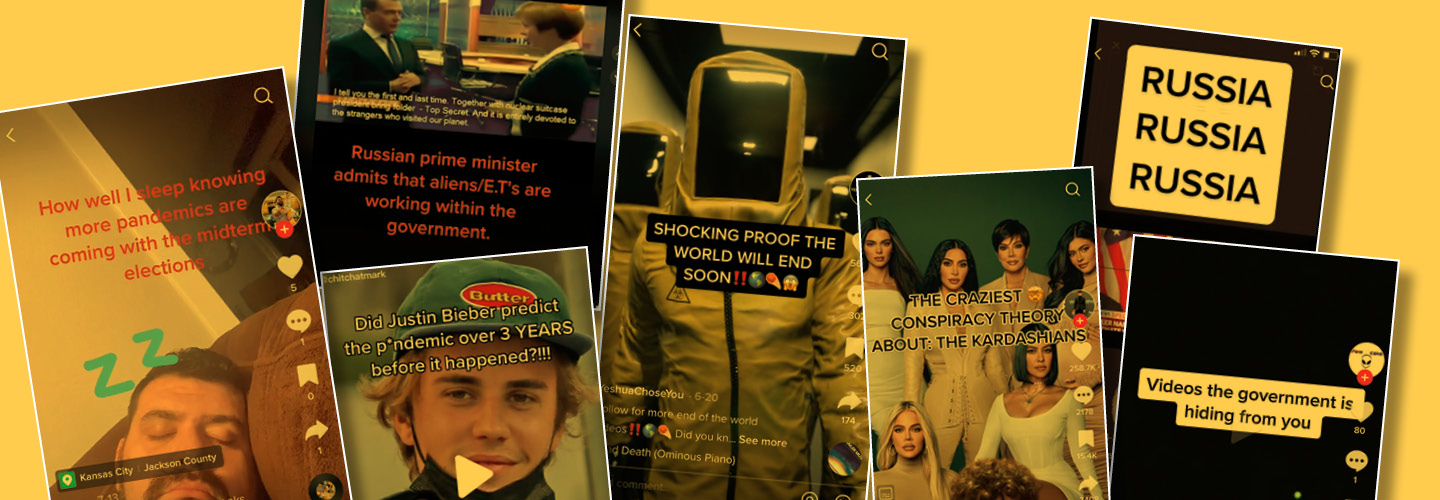

But while TikTok can be a great option to learn about political topics that interest you, there’s a problem: It’s also full of dangerous misinformation, experts say.

During recent elections around the globe, this misleading information has caused real trouble. In Germany, for example, TikTok accounts impersonated prominent political figures during the country’s last national election. In Colombia, TikTok posts allowed a woman to masquerade as a candidate’s daughter. In the Philippines, TikTok videos amplified myths about the country’s former dictator and helped his son win the country’s presidential election.

Now the U.S. is facing similar issues as November’s midterm elections approach. According to researchers, the same qualities that allow TikTok to fuel viral dance fads—the platform’s enormous reach, the short length of its videos, its powerful but poorly understood recommendation algorithm—can also make inaccurate claims difficult to contain.

Conspiracy theories are widely viewed on TikTok, which globally has more than 1 billion active users each month. Although the platform has blocked some political topics, such as the #RiggedElection hashtag, there are still videos urging viewers to vote in November while citing debunked rumors. For example, TikTok posts have garnered thousands of views by claiming, without evidence, that predictions of a surge in Covid-19 infections this fall are an attempt to discourage in-person voting.

TikTok is quietly becoming a political force all over the world. In the United States, more people, especially teens, are using the platform. They rely on it for election information, news updates, and fact-checking.

TikTok can be a great option to learn about political topics that interest you. But there’s a problem: Experts say that the platform is also full of misinformation that could be harmful.

During recent elections around the globe, this misleading information has caused real trouble. For example, TikTok accounts posed as key political figures during Germany’s last national election. In Colombia, TikTok posts allowed a woman to pretend to be a candidate’s daughter. In the Philippines, TikTok videos fueled myths about the country’s former dictator and helped his son win the country’s presidential election.

Now the U.S. is facing similar issues as November’s midterm elections approach. The same qualities that allow TikTok to fuel viral dance fads can also make inaccurate claims hard to contain. These qualities include its enormous reach and its powerful but poorly understood recommendation algorithm.

TikTok has more than 1 billion active users from across the globe each month. As a result, conspiracy theories are widely viewed on the platform. The platform has blocked some political topics, such as the #RiggedElection hashtag. Still, there are videos urging viewers to vote in November while repeating rumors that have been disproven. For example, there have been predictions that Covid-19 infections will surge this fall. TikTok posts have gotten thousands of views by claiming these predictions are an attempt to block in-person voting. And these claims have been made without evidence.