Ohio is so often a key battleground in presidential elections that many politicians have dubbed it “the swingiest of swing states.” That’s because the state’s population is almost evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats, and candidates from both parties have a history of winning statewide contests—often in close races.

But you wouldn’t know that from looking at the balance of power in Ohio’s state legislature or in the state’s congressional delegation. For the past decade, Ohio has sent 12 Republicans and 4 Democrats to Washington to serve in the House of Representatives. In the Ohio legislature, Republicans hold about two-thirds of the seats in the House and about three-quarters in the Senate.

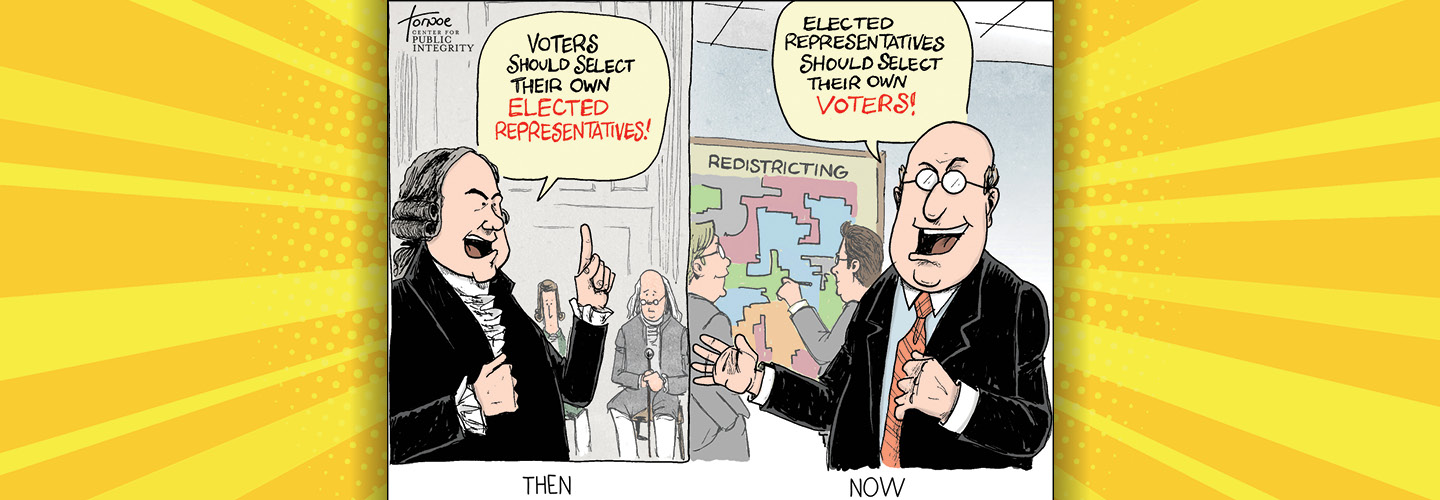

How is that possible? In a word, redistricting, which is the process of redrawing election district maps. There’s a long history in the U.S. of politicians—both Democrats and Republicans—drawing maps that aren’t fair in order to give themselves an advantage.

Ohio is often a key battleground in presidential elections. That’s why many politicians have dubbed it “the swingiest of swing states.” What’s behind that? Ohio’s population is almost evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats. Candidates from both parties have a history of winning statewide contests. And the races are often close.

But you wouldn’t know that from looking at the balance of power in Ohio’s state legislature or in the state’s congressional delegation. For the past decade, Ohio has sent 12 Republicans and 4 Democrats to Washington to serve in the House of Representatives. In the Ohio legislature, Republicans hold about two-thirds of the seats in the House and about three-quarters in the Senate.

How is that possible? In a word, redistricting, which is the process of redrawing election district maps. There’s a long history in the U.S. of politicians—both Democrats and Republicans—drawing maps that aren’t fair. They do so to give themselves an advantage.